Back in early March, without much fanfare, the U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 1106, entitled the “Helping Families Save Their Homes Act of 2009”, which contained a “Servicer Safe Harbor” provision that would allow servicers to disregard bondholders’ contract rights when modifying mortgages. It now appears that the bill will not fly so easily through the Senate (keep tabs on the progress of this bill here at govtrack.us or here at thomas.loc.gov).

Back in early March, without much fanfare, the U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 1106, entitled the “Helping Families Save Their Homes Act of 2009”, which contained a “Servicer Safe Harbor” provision that would allow servicers to disregard bondholders’ contract rights when modifying mortgages. It now appears that the bill will not fly so easily through the Senate (keep tabs on the progress of this bill here at govtrack.us or here at thomas.loc.gov).

On March 25, 2009,

Bill Frey, the head of hedge fund

Greenwich Financial Services LLC, gave a talk in Washington to more than 30 money managers with stakes in the $6.7 trillion mortgage bond market, warning them that government efforts to assuage the housing crisis will undermine debt contracts and do more harm than good. Also presenting at the bond investor conference, which was attended by, among others, representatives from Royal Bank of Canada’s Voyageur Asset Management Inc. and Thrivent Financial for Lutherans, were David Grais, the lawyer who represents Frey in his

suit against Countrywide (which may have prompted this bill), and Laurie Goodman, an analyst at Amherst Securities and UBS AG’s former fixed income research chief. According to this interesting

report from Bloomberg, as a result of this meeting, a group of investors with residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) holdings totaling more than $100 billion hired Patton Boggs LLP, Washington’s biggest lobbying firm, to gear up for the fight in Washington over the pending legislation.

As part of this new lobbying effort, Grais and his firm, Grais & Ellsworth LLP, have issued a

press release entitled “Five Reasons Why ‘Servicer Safe Harbor’ Would be Bad for America.” This release does an excellent job of explaining the perverse consequences of the bill, while capturing in straightforward terms the various reasons why mortgage bondholders oppose this legislation, despite its purported purpose of “helping families save their homes.” For one, bondholders negotiated for the valuable contract rights at issue, which impose the cost of modifications on servicers (Grais identifies these servicers as “mainly the Big Four Banks, Bank of America, Citibank, JP Morgan and Well[s] Fargo”), as a precondition to investing their money into RMBS. Bondholders secured these rights because they knew that modifications would otherwise come out of their bottom line, not from that of the servicers who had the discretion and authority to conduct loan modifications. Allowing servicers to abrogate these rights would unfairly place the financial burden of modifications on bondholders and thereby discourage future investment in the RMBS market.

A second reason is that, while servicers don’t hold many of the senior or first-lien mortgages on their books, they do hold many junior or second-lien loans. By law and/or contract, second liens are often required to be modified before first liens. Allowing servicers to modify first liens before or in lieu of second liens improves these banks’ bottom lines at the expense of their investors.

Third, the legislation offers cash incentives of $1,000 per loan modified and other incentives to the servicers, allowing the entities that made a fortune from lending and then passing off loans that borrowers couldn’t afford to further profit from going back and attempting to correct their mistakes.

When Grais runs into a bit of trouble is when he claims that the Servicer Safe Harbor “would not help homeowners.” Grais’ argument is that servicers will often increase the principal balance of loans they modify by adding the extra fees they charge borrowers who fall behind. He contrasts this with investors’ plan for modifications, which he claims will “reduce principal to give homeowners equity.” What Grais doesn’t tell us is how many mortgages will be modified if the Servicer Safe Harbor is passed versus under the investors’ plan. Ultimately, most homeowners would choose to stay in their homes, even at the expense of an increase in principal, over having to leave because they couldn’t afford their current mortgage payments. And while the investors’ plan may favor lowering principal balances, the likely consequence will be a higher monthly payment than under the banks’ modification plans.

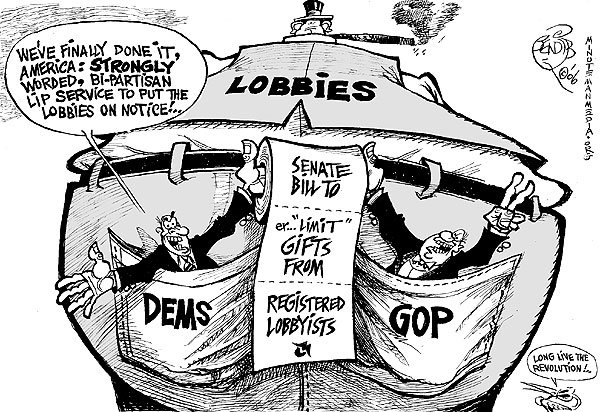

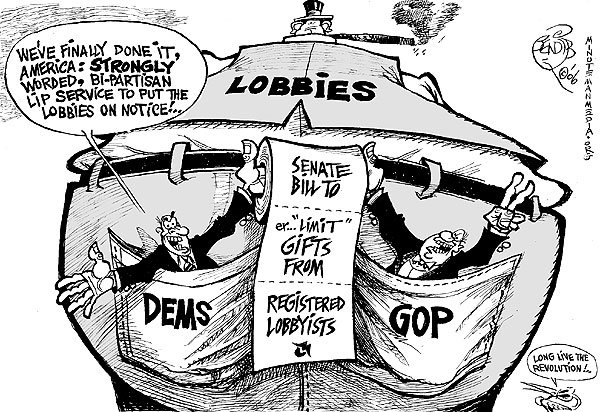

In the end, there is little argument that the Servicer Safe Harbor will likely result in more mortgages being modified than before, something that investors, banks, politicians and homeowners would all agree is a good thing. The real fight is over who should pay for these modifications, and Grais and Frey would be wise to keep the focus on this debate. Investors believe that either the government or the banks should bear the costs, while the banks would like nothing more than to place the burden on the investors. Washington now appears likely to be the one to decide this issue, and as is often the case (unfortunately) when it comes down to politics, the answer will be in large part a result of how much money has been spent on lobbying and campaign contributions. Just look at the two politicians who introduced the “Helping Families Save Their Homes Act” in the House, Paul E. Kanjorski (D-PA) and Michael N. Castle (R-DE). Bank of America (which now owns Countrywide) was the

second biggest contributor to Castle’s campaign during the 2007-2008 election cycle, making Castle

one of the top 10 beneficiaries of BofA last year (behind only presidential candidates). Kanjorski was the

second biggest recipient of Countrywide campaign contributions since 1989. Clearly, BofA expects (and has received) a tangible return on its investment.

Yet, there is already evidence that bondholders’ lobbying efforts are countering those of the big banks and paying significant dividends. Though the mainstream media had up to this point largely ignored the Servicer Safe Harbor issue,

Gretchen Morgenson, a columnist for the New York Times,

published a column last week discussing the “unintended consequences” of the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act and loan modifications in general. Morgenson notes, correctly, that while “big-time speculators and market sophisticates” make up part of the group of investors who would be harmed by this bill, the group also includes ordinary individuals who invested in mutual funds and other professionally managed accounts that acquired RMBS as part of their portfolios. Ultimately, if votes mattered more than dollars (a debatable proposition), it would be this argument, with its populist appeal, that

would carry the day in Washington.

Thank you to David Proman and Chris Corio who contributed helpful insight and research to this story – IMG.

Back in early March, without much fanfare, the U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 1106, entitled the “Helping Families Save Their Homes Act of 2009”, which contained a “Servicer Safe Harbor” provision that would allow servicers to disregard bondholders’ contract rights when modifying mortgages. It now appears that the bill will not fly so easily through the Senate (keep tabs on the progress of this bill here at govtrack.us or here at thomas.loc.gov).

Back in early March, without much fanfare, the U.S. House of Representatives passed H.R. 1106, entitled the “Helping Families Save Their Homes Act of 2009”, which contained a “Servicer Safe Harbor” provision that would allow servicers to disregard bondholders’ contract rights when modifying mortgages. It now appears that the bill will not fly so easily through the Senate (keep tabs on the progress of this bill here at govtrack.us or here at thomas.loc.gov).