As first reported by Reuters on Wednesday, and as further detailed by Bloomberg today, the Investor Syndicate has finally begun to emerge from the shadows and give securitization trustees a hint at what’s coming. According to Talcott Franklin, the Dallas attorney who is spearheading the Syndicate, the group sent letters to some of the major trustees of mortgage-backed securitizations, detailing the holdings of the group and urging trustees to help them enforce servicing breaches and pursue buybacks of improperly-originated loans. The letters have not yet been made available, as the group appears to be continuing to closely guard the identity of the investors involved.

Franklin would only say that the members of the Syndicate are investors representing over $500 billion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) holdings, which would account for over one-third of the $1.5 trillion private-label MBS market. Franklin was formerly with the lobbying group of the Washington, D.C.-based law firm, Patton Boggs, that was involved in bondholders’ lobbying efforts over the Servicer Safe Harbor, but reportedly left the firm this year to head up the Investor Syndicate.

Franklin would only say that the members of the Syndicate are investors representing over $500 billion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) holdings, which would account for over one-third of the $1.5 trillion private-label MBS market. Franklin was formerly with the lobbying group of the Washington, D.C.-based law firm, Patton Boggs, that was involved in bondholders’ lobbying efforts over the Servicer Safe Harbor, but reportedly left the firm this year to head up the Investor Syndicate.

As discussed in prior posts (here and here), the Syndicate’s initial goal was to amass enough representation in a material number of securitizations to meet the 25% or 50% ownership thresholds imposed by the trust agreements, thereby acquiring the right to petition the trustees of those deals to take action. From Franklin’s statements, it appears that this first step has been accomplished, as he has represented that the Syndicate owns bonds giving them 25% of “voting rights” in over 2,300 deals, 50% in more than 900 deals, and 66% of the bonds in more than 450 deals.

Assuming this is true, the letters sent on behalf of the Syndicate this week should be viewed as merely an opening salvo. It is only a matter of time before the Syndicate begins issuing communications to trustees identifying specific instances of servicer misconduct or defects in the underwriting with respect to particular loans. These instances of misconduct, also known as “defaults,” will change the responsibilities and incentives of the parties dramatically. Once trustees are made aware of specific defaults by bondholders owning the requisite percentage of voting rights, the trustees become essentially fiduciaries of the bondholders, and acquire obligations to take steps to remedy those defaults. Should they fail to do so, they may be fired or sued.

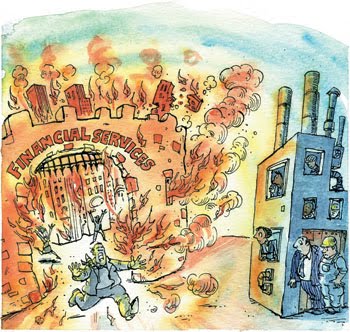

To those invested in the Big Four banks, which originated and now service huge percentages of the loans underlying these private-label securities, this next step will be the equivalent of yelling “fire” in a crowded movie theater. Up to now, banks have been able to drag their collective feet in recognizing losses associated with the profligate lending practices of 2005-2007. When banks originated mortgages and sold them into securitizations, they made representations and warranties regarding the quality of the underwriting and the guidelines they followed. Should the Investor Syndicate be able to acquire the servicing and loan files associated with these mortgages and find breaches in those reps and warranties (as Freddie and Fannie are trying to do now through their subpoena powers), banks will be inundated with repurchase requests. And as the media and government officials have only recently begun to recognize, banks have consistently under-reserved for the losses they will likely face from investor buyback obligations.

Further, in their role as servicers, these same banks have been slow to foreclose on hopelessly delinquent borrowers, as they were rife with conflicts of interest based on their second lien holdings. Servicers have instead been content to rack up late fees while investors remained unorganized and the normally passive securitization trustees had no incentive to act. Without active trustee enforcement of servicing obligations, the banks have also been able to modify loans as they pleased, irrespective of whether such workouts were in the best interests of bondholders, because trustees would not enforce servicer obligations to obtain the approval of the investors (see articles on the Greenwich Financial lawsuit against Countrywide for more background on this issue). However, once trustees are compelled to go after these servicing breaches (or are fired and replaced by friendly trustees if they don’t), the banks will be liable for additional losses caused by their failure to service loans in accordance with bondholder wishes.

All this is to say that the financial landscape will change drastically in the coming month as the Investor Syndicate moves forward with its plans. To drop a shameless Counting Crows reference, the MBS world may look very different in “August and Everything After.”