by Steve Ruterman, guest blogger

It has been four years since the onset of the epic economic and capital markets fiasco known as the housing crash, and this crisis is far from over. Because the housing and mortgage finance industries are so important to the nation’s economy, we simply can’t afford to wait until we reach the endgame before we reach an understanding of what happened and why.

There are a lot of explanations out there already. For example, Michael Lewis in The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine says the crisis took place because the big banks ceased operating as private partnerships taking prudent risks with the partners’ money. Instead, they became public companies, and began taking undue risks with public shareholders’ money. Maybe this is so, but there were plenty of bubbles, crashes, panics and insolvent banks in the country’s history prior to the public ownership of banks.

Adam Levitin and Susan Wachter, in “Explaining the Housing Bubble,” argue that the market bubble and subsequent crash were due to an oversupply of housing finance, which was caused in turn by the explosive growth of the non-agency securitization market. The oversupply occurred because the complexity and heterogeneity of private label mortgage securities permitted bankers to game investors, who were unable to price their risks correctly. The authors identify the standardization of mortgages and securitizations as the means of avoiding future fiascos. It would be interesting to see how the authors explain the current problems associated with GSE efforts to mitigate risks via standardized mortgages and securitizations, which they’ve had for over 30 years since Fannie issued its first pass-through in 1981.

Though neither of these explanations seems entirely satisfying on its own, there is no reason to expect the various explanations to be mutually exclusive. Instead, each adds important detail to the complex phenomenon that was the housing crash. No doubt, the crash had many fathers.

It is possible, however, that the causes of the crash are relatively simple to identify and understand, even though future remedies may not be. One of the simplest explanations can be found in the business models of the big mortgage lenders. Let’s take Countrywide to be our exemplar, and focus in on the 2005–2007 time period. Remember that Countrywide concentrated on the refinance (“refi’) segment of the market.

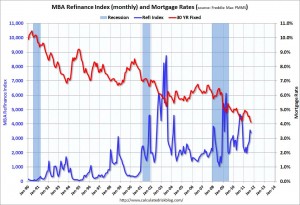

Taking note of the dramatic slowdown in refis after 2003 (see chart at right courtesy of Calculated Risk), Countrywide officers were quite vocal in airing their concerns about maintaining and growing their share of the stagnant mortgage market. How was Countrywide, a publicly traded mortgage colossus with over a trillion dollars in existing mortgages, going to grow its earnings per share when the market was not growing? Given its size and scale, the only way to do it was to market additional loans to its existing customers or to relax its credit underwriting standards for each of its loan product categories, so that it could lend to borrowers who would not have qualified for credit in years past. Apparently, Countrywide did both.

The following is an excerpt from the complaint AIG filed against Countrywide, et al., on August 8, 2011:

In a conference call with analysts in 2003, [CEO Angelo] Mozilo made Countrywide’s market share objectives explicit, stating that his goal for Countrywide Financial was to “dominate” the mortgage market and “to get our overall market share to the ultimate 30% by 2006, 2007.” At the same time, Countrywide made public assurances that its growth in originations would not compromise its strict underwriting standards. Indeed, Mozilo publicly stated that Countrywide would target the safest borrowers in this market in order to maintain its commitment to quality.

[Author’s Note: Allegations made by plaintiff’s counsel in a complaint are what they are.]To increase its market share, Countrywide instituted an aggressive “matching” program that effectively ceded its “theoretical” underwriting standards to the market and resulted in a proverbial race to the bottom. Under Countrywide’s “matching” policy, Countrywide would match any product that a competitor was willing to offer. A former finance executive at Countrywide explained: “To the extent more than 5 percent of the [mortgage] market was originating a particular product, any new alternative mortgage product, then Countrywide would originate it …

The point from this is that it’s not necessary to construct complex explanations of the mortgage market’s collapse. It is sufficient to understand the relatively simple business models of the boom’s beneficiaries.

However, for a comprehensive analysis of business models and the many other factors which led to the collapse of the mortgage market, I would recommend Way Too Big To Fail: How Government and Private Industry Can Build a Fail-Safe Mortgage System from Greenwich Financial Press. The book, written by William A. Frey and edited by The Subprime Shakeout’s Isaac Gradman, is now available on CreateSpace and Amazon. Therein, Frey draws on 30 years of experience in structured finance to detail both the causes of the crisis and the reforms and steps to be taken to bring private investment back to the housing market.

Frey appears to share my belief that we can’t recover from this crisis until we fully understand its causes. And at the end of the day, the main culprit he identifies is similar to the one I detail above–misaligned incentives for those creating mortgage securities. I won’t give too much away, but having read an advance copy of this work, I can say that Frey’s analysis is fundamentally correct and that his recommendations are realistic and necessary. I would highly encourage the read for anyone seeking to understand the flawed business models that got us into this mess and, more importantly, what we can do to dig ourselves out.

Steve Ruterman is an independent consultant to institutions and institutional investors with significant RMBS exposures and a fan of The Subprime Shakeout. He recently retired after a 14 year career with MBIA Insurance Corporation, during which he terminated over 20 mortgage loan servicers. Mr. Ruterman welcomes your comments, and can be reached by email at Steve.Ruterman@yahoo.com.

[Updated on 11/4 to reflect that Way Too Big to Fail has been released and is now available – IMG]