After a hiatus over the holidays, I return with Part IV of this five-part series on my experiences during a recent book tour to promote the release of Way Too Big to Fail: How Government and Private Industry Can Build a Fail-Safe Mortgage System. Use the following links to read Parts I, II, and III.

I again woke before dawn on the third day of our East Coast tour to promote the release of Way Too Big to Fail (WTBTF). Over the last two days, author Bill Frey and I had met with numerous individuals in finance, academia and the media, but today would be different. That’s because today we would be flying directly into the mouth of the beast—Washington D.C.—to meet with some of our nation’s elected officials.

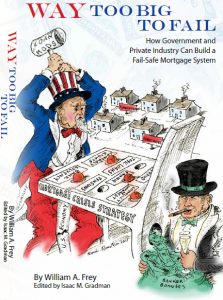

The cover of WTBTF (see left or visit the book’s Facebook page for more detail) depicts a cartoon of Uncle Sam playing a game of Mortgage Crisis Strategy Whack-A-Mole, futilely swinging the hammer of “Loan Mods” at the various mortgage problems that pop up, while the “U.S. Economy” leg of the game’s table cracks and money flows out of the back of the machine into a bag labeled “Banker’s Bonuses.” Suffice it to say that WTBTF’s cover does not paint the most complimentary picture of Washington’s efforts to solve the mortgage crisis, so it would be interesting to see what the folks at Capitol Hill would say when we handed them a copy.

Our flight into D.C. arrived around 8:30 AM and we jumped on the Metro to get to our first meeting of the day: with Georgetown Law Professor Adam Levitin. Levitin was one of the few academics who consistently had been willing to speak the truth regarding the depth of the banks’ problems stemming from their subprime origination and securitization activities.

In one particularly memorable instance, Levitin was hired by Citigroup as a guest speaker and asked to give his assessment of problems associated with improper foreclosures, robosigning and broken chain of title. The resulting report, entitled “Foreclosures Gone Wild,” was released by Citigroup despite being, in Citi’s own words, “one of the bleaker portraits of these matters and their ultimate resolution.” It then summarized Levitin’s findings as follows:

[i]t appears that in many instances during the mortgage securitization process over the past few years, the paperwork was not properly transferred. If the paperwork was not transferred in the legally required manner, it raises questions not only about who owns the mortgages in question but also about the validity and tax exempt status of the trusts in which the mortgages reside.

Not surprisingly, this report and it’s conclusions made waves instantly among commentators and analysts, prompting me to write that someone at Citi was likely on the Budweiser Hot Seat for having hired Levitin to be the featured guest in the first place. Citigroup’s legal team ultimately pulled the report from the Internet, stating that it was simply standard practice to “investigate any misuse of Citi’s intellectual property,” but the damage had been done. Interestingly, the report can still be found here and here.

I had first started talking to Levitin in early 2011 when he linked to some of my articles on Credit Slips. Later, I asked him to read an advanced copy of Way Too Big to Fail and offer us his thoughts. Despite his busy schedule, he had made the time to do so, and reported back that he thought the book was great. He ultimately provided extensive feedback, both positive and constructive, as well as a blurb, which now appears on the back cover (you can read Levitin’s blurb, along with other testimonials, here). Frey, Levitin and I had since had several productive conversations, and everyone seemed to benefit from the ongoing exchange of ideas.

I was excited to finally meet in person the man who had been willing to tell the banks what he thought, not what they wanted to hear. I sat down in Levitin’s office at Georgetown Law Center and took a quick look around. The décor did little to suggest that Levitin was anything other than the typical law professor. His bookshelves were lined with legal texts and memorabilia from some of the most famous legal cases (he even had a framed certificate of original shares in Erie Railroad from the famous choice of law case Erie Railroad v. Tompkins).

Yet, Levitin was not the typical law professor, consumed solely with esoteric questions about subtle distinctions in legal interpretation or trends in Supreme Court precedent. Levitin had a decidedly macro perspective that evinced a much deeper interest and understanding in global finance and politics than most of his peers. And, importantly, he was not afraid to share his views on this diverse array of topics in both published papers and on the Credit Slips blog.

Today, Levitin was focused on trying to understand why Bank of America had moved its derivatives into a depository, and what this revealed about its deeper problems. In particular, he was focused on the gap between BofA’s then-book value of about $220 billion and its then-market cap of about $70 bn. This, he felt, could only be explained by the market’s perception that BofA had bogus assets and/or unrecognized liabilities. But in that case, why had the bank made such a large investment in the bonds of troubled European sovereigns (the so-called PIIGS)?

Frey had a response: the banks will use these positions to hold the PIIGS, and the U.S. Treasury, hostage. “Remember that scene in Blazing Saddles,” Frey said, “where the Sherriff comes to town and is about to be lynched because he’s black? So he holds a gun to his own head and says, ‘Don’t make a move or the black guy gets shot!’?” [This was the first I knew that Frey was a Mel Brooks fan.] “That’s essentially what the banks are doing. They’ll go to Geithner and say, ‘Now that we hold these bonds, you better bail out the PIIGS or they’ll take us down with them and you’ll have a much bigger problem on your hands.’”

This was a point that Frey had also made in WTBTF – that it was dangerous for a country to let a bank or any other entity exist without capital but with implied government backing. Such a state of affairs could lead to reckless “double-or-nothing” type bets that, while rational for the bank, would be grossly detrimental to the country and the taxpayer in the long run.

Levitin was intrigued. A week later, he published this article on Credit Slips entitled, “Is Bank of America Gambling on Resurrection (or Is BoA Holding the US Hostage)? Therein, he explored further the possibility of the banks using European debt to hold the U.S. over a barrel.

That day in his office, we also spoke about Way Too Big to Fail, and Levitin offered some suggestions of other people in the industry who might benefit from reading the book or have valuable feedback. He reiterated that he thought WTBTF was a valuable resource and that the folks in Washington should take notice, though there was no guarantee they would. “Everyone else seems to want to stick it to the banks these days and see someone go to jail,” Levitin said. “When will Washington get that?”

We were determined to find out. We said goodbye to Levitin, as he was heading out to teach a first year class on contract law, and we headed to Capitol Hill. We had a full slate of meetings planned that day with the staffs of a half dozen congressmen. Frey had done this sort of thing before, but it was my first time, and I was apprehensive about what I might encounter. Exactly how far behind the curve were our elected officials?

Our first meeting did little to reassure me. We met with the “housing policy expert” on the staff of a senator who will remain nameless. The staffer was a spitting image of Frey’s description in WTBTF of most staffers he had met while lobbying against the Servicer Safe Harbor:

[f]or those unfamiliar with the lobbying process, as I was at the time, it turns out that one rarely gets to meet with any elected officials. Instead, each official is usually represented by a young adult with a freshly minted law degree who, while ostensibly well intentioned, is a self-described “policy wonk” with little experience in the subject matter. (WTBTF at xxxvi)

After handing the staffer a copy of our book, our first order of business was to understand how much the staffer already knew so we could decide where to start. “You can rebuild securitization privately through reforming the standard PSA,” Frey began, “but it can be done faster and more uniformly by having the government enact certain measures that get the ball rolling in the right direction.”

“What’s a PSA?” the staffer responded. This came as a bit of a surprise, as a housing policy expert probably should have been familiar with a Pooling and Servicing Agreement, the central contract governing a mortgage securitization. It was then that Frey and I realized the enormity of the task that lay ahead – educating our nation’s decision-makers and their staffs about the complexities of housing finance that stood in the way of housing market recovery.

But of course, the reason that we had published WTBTF in the first place was to provide an educational tool to those who wished to improve this very system. This necessarily involved teaching those without a background in structured finance about the history and legal underpinnings of securitization, its inherent conflicts of interest, and the steps that should be taken if it was to be rebuilt so that it survived.

Patiently, we spent the next hour explaining some of these concepts to the staffer. At the end of this meeting, we felt fairly confident that the staffer knew far more about mortgage backed securities than he or she had going in, but we still knew we had barely scraped the surface. This was certainly going to be no easy task, but it was one that we were excited about finally undertaking in earnest.

It turns out that most of the staffers we met that day were more knowledgeable about mortgage issues than the staffer from our first meeting, but there were still plenty of gaps in their knowledge that we felt we could fill in. A common refrain we heard was that most congressmen had one staffer who was his or her “housing policy expert” and one staffer who was their “finance expert,” but that “housing finance” fell somewhere in between. This was more than a little disconcerting, considering that this market was as large as $11 trillion at its peak and should hardly have been considered a niche expertise, let alone something that fell through the cracks.

Later in the day, we had the pleasure of meeting with a few staffers who understood many of the issues plaguing housing finance and the importance of rebuilding this market. It was refreshing to speak at last to folks in Washington who were on the same page about the need for reform in this area, and who could speak intelligently about the challenges they faced in trying to do so. While I won’t disclose their names, as I don’t want to suggest a partisan bent to this plainly bipartisan issue, I will say that this understanding of the issues is reflected in the public statements and legislation that has been authored by their offices.

It made me realize that behind every reasonably-coherent statement by an elected official on a matter of housing finance is a wise staffer or two that actually gets it. After handing out copies of WTBTF to more than a dozen such staffers today, I’m hoping that we can at least add a few more individuals’ names to those ranks in the coming months.

Follow @WTBTF on Twitter for real time updates on the book and its impact.