“As long as the roots are not severed, all is well. And all will be well in the garden.”

“As long as the roots are not severed, all is well. And all will be well in the garden.”

– Chance the Gardener, Being There (1979)

With Judge Barbara Kapnick announcing earlier this month that the approval hearing in Bank of New York Mellon’s (BNYM) proposed $8.5 billion Article 77 settlement over Countrywide bonds will take place in May 2013, this next year will be truly one of reckoning for mortgage investors and the U.S. mortgage market as a whole. Though Her Honor’s proposed timetable may be a bit ambitious, what is clear is that the window of opportunity for investors be made whole for the toxic waste they were sold is finite and rapidly shrinking.

In the case of Countrywide, the end game will depend on the evidence that objecting investors can uncover prior to the approval hearing that might demonstrate that BNYM was conflicted or that its assumptions were unreasonable, both of which would suggest that the settlement number is too low. For example, the Steering Committee of objecting investors has now sought to intervene in MBIA v. Countrywide to persuade Judge Bransten to remove Countrywide’s confidentiality designations from evidence that MBIA will be presenting to support its summary judgment motions. Should these documents become public, they would not only encourage Bank of America to settle its 4-year battle with the bond insurer, but they would provide objecting investors in the separate Article 77 action with evidence that might undermine Bank of New York’s assumptions that BofA could ring fence Countrywide.

Meanwhile, the end game scenarios for MBS issuers other than Countrywide will depend on how well investors can get organized over the next six months to a year before the expiration of New York’s six-year statute of limitations on rep and warranty claims.

I have been covering these developments for nearly five years, and blogging about them for four, and I can say with little hesitation that this year will tell us more about the ultimate subprime shakeout than any since the onset of the Mortgage Crisis. The outcome of BNYM and BofA’s ambitious global settlement as well as investor efforts to file claims before the statutory deadline should lead to a flurry of activity before this time next year, giving us some degree of closure regarding who will bear the losses for the irresponsible lending of 2006 and 2007. With these developments already starting to unfold, I thought it was high time for my long-promised article on investor end game scenarios.

A Quick Look Back

I launched this blog in July 2008 (link to my first post) in part to help keep readers informed of the latest developments in a market that affects us all in one way or another, and usually in more ways than one. If you pay taxes, own investments or pay a mortgage in the U.S., you have and continue to be impacted by the fallout from this country’s worst housing crisis since the Great Depression.

But another purpose of this blog was to try to understand what investors were doing about this mess, and if I could, to help push investors towards taking proactive steps to help get this country back on track. With the government response sorely lacking in cohesiveness and sophistication, only concerted action by investors could restore the integrity of our mortgage market, an essential cog in the economy that was valued at $11 trillion at its peak.

I came at this issue from a background in mortgage insurance litigation, through which I was exposed to shocking truths about how the subprime and Alt-A sausage was made in the years leading up to the crash. We had been able to obtain favorable results for mortgage insurance clients based on the strength of their contractual representation and warranty claims that held lenders and issuers to concrete underwriting standards. But I kept asking myself, if mortgage insurers were having success suing and/or forcing settlements over loans that didn’t meet lending guidelines, why weren’t investors doing the same?

Four years later, with only a fraction of potential investor suits having been pursued, I have gained some of the answers to that question, but none are satisfactory. Yes, investors are conservative by nature, they usually wish to avoid the spotlight, and they are (rightfully) skittish about suing the powerful banks with whom they do business on a regular basis. The procedural hurdles in their contracts are onerous, the path of litigation is long and costly, and the prize at the end of the road is uncertain and difficult to quantify.

All these things are true, and yet the returns from this type of litigation could be enormous – far exceeding the returns investors could achieve just about anywhere else in the market. More importantly, I would argue that this type of litigation engenders critical redistribution of wealth from banks to investors, which both deters banks from engaging in shoddy lending and securitization practices, and helps to encourage investors to return and support a private mortgage market in the future. Still, nobody ever said that doing the right thing and unwinding one of the most complex and extensive Ponzi schemes in history would be easy.

An Unexpected Source of Inspiration

One of the great things about living in Petaluma (other than getting to watch our boys finish third in the Little League World Series this past weekend – so proud!) is that most homes have decent-sized backyards and there’s great weather for gardening. Each year, I like to grow a few standards – tomatoes and jalapeños for homemade salsa, at a minimum – and a few novelties, just to keep things interesting. This year, I tried my hand at Japanese eggplant, curly kale, and tomatillos. I even grew some padron peppers, known as the Russian roulette peppers because every half dozen or so are deadly spicy, which turned out to be a hit in my family. This year, as in years past, some plants flourished, while others never seemed to catch on.

I was working in my garden this past weekend, getting a healthy reprieve from mortgage crisis litigation, when I stopped to evaluate a couple of potted herbs that had once been strong, but that had for some time been languishing in various states of poor health. I had tried everything on these – watering them more, watering them less, giving them more sun, giving them less sun, cutting them back, letting them grow – but nothing seemed to work. The stalks had become ossified, the leaves rust-colored, and there was little growth or production to speak of.

I decided I might try transplanting these sickly specimens, but when I removed the pots from around the root balls, I realized that their roots had withered and died, and these plants were beyond help.

It was only then, when I finally decided to let those plant go, and went out and bought new, vibrant replacement plants, that I realized what a drag the old plants had been on my garden. Sure, it hadn’t “cost” me anything in the monetary sense to prop these plants up, beyond perhaps the cost of the water I poured into their pots. But in reality, there were significant non-monetary costs that had to be taken into account.

There were the favored places in the garden that got the most sunlight that the plants had been occupying, there was the time and effort that I put into keeping them alive, there was the emotional drag of seeing the plants failing to recover day after day, and there were the opportunity costs of not having fresh herbs to use because I didn’t want to go out and buy replacements when the old plants in my garden were still technically alive. Suddenly, a light bulb went off.

My saga with my plants on life support was the perfect metaphor for the societal costs of propping up the “too big to fail” (TBTF) banks and allowing fatally wounded “zombie” banks to continue to suck scarce resources from the economy. Just as it pained me to give up on plants that had once been productive, the politics surrounding “too big to fail” banks make regulators irrationally averse to allowing nature to run its course and take down sickly financial institutions. The fear is that the interconnectedness of the market, just like the interconnectedness of a root system, means that allowing a major financial institution to fail will disrupt the entire market. But the alternative brings its own costs that must be taken into account, such as the creation of perverse incentives for anti-competitive and inefficient behavior.

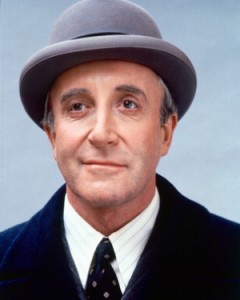

Of course, this wasn’t the first time someone had drawn the analogy between botany and economic health. I immediately thought of the 1979 movie Being There (based on the book by Jerzy Kosinski), featuring Peter Sellers in a unique role as the simpleton gardener who gets mistaken for a brilliant sage (watch original trailer here).

Of course, this wasn’t the first time someone had drawn the analogy between botany and economic health. I immediately thought of the 1979 movie Being There (based on the book by Jerzy Kosinski), featuring Peter Sellers in a unique role as the simpleton gardener who gets mistaken for a brilliant sage (watch original trailer here).

Knowing nothing about the outside world except what he had seen on TV and learned in his garden, Chance the Gardener wanders out into the world to become known as Chauncey Gardner, whose simple statements about gardening come to influence national economic policy. I had not seen the movie in many years, so I decided to rent it, and was bowled over by its continued relevance. Take the following exchange:

Chance the Gardener: In the garden, growth has it seasons. First comes spring and summer, but then we have fall and winter. And then we get spring and summer again.

President “Bobby”: Spring and summer.

Chance the Gardener: Yes.

President “Bobby”: Then fall and winter.

Chance the Gardener: Yes.

Benjamin Rand: I think what our insightful young friend is saying is that we welcome the inevitable seasons of nature, but we’re upset by the seasons of our economy.

This axiom immediately called to mind my economics classes in college, in which the pejorative word “recession” was rarely used when describing down cycles in the market. Instead, these downturns were referred to as “corrections,” a word with a much more positive connotation.

The idea was that down cycles were necessary and ultimately beneficial parts of the business cycle, as they corrected inefficiencies in the market by exposing and eliminating the weakest players. This, in turn, cleared the way for new, more efficient players to enter, enabling greater long-term growth. In other words, to paraphrase Jefferson, the tree of capitalism must be refreshed from time to time by the blood of insolvency.

An Economy on Life Support

Unfortunately, during this recent recession, little has actually been “corrected” in the U.S. market, and it’s a big reason we continue to languish in a tepid economy, bouncing along the bottom. The continued lethargy in the housing market across most of the country is one of the primary culprits, and this, in turn, can be blamed on a failure to deal effectively with distressed properties and the failure to correct fundamental problems with housing finance that might pave the way for the return of the private market.

Bill Frey and I published Way Too Big to Fail precisely to address and offer solutions for these ongoing problems, but few of these suggestions have been implemented as of this writing (I would note that Redwood Trust, one of the few funds that has been issuing MBS in the last few years, has implemented several reforms in its securities that mirror those discussed in the book, and has demonstrated solid performance as a result).

The truth remains that loan aggregators and sellers have not been forced to pay for the harm they have inflicted on the economy – not in any meaningful sense. Sure, some of them got caught holding the bag with some of these toxic assets on their own books when the music stopped, and some have settled with certain aggressive investors or insurers, but they have not been held accountable for the bulk of the toxic assets they sold during the Boom Years.

And what did these issuers do that was so wrong? Weren’t they victimized like the rest of us when the world unexpectedly fell apart?

As I’ve gone into at great length in prior posts, at a minimum, loan aggregators and sellers (i.e. most of this country’s largest banks and investment banks) sold over a trillion dollars’ worth of securities backed by loans that were nowhere near the quality that they represented (let’s use the technical legal term “crappy loans”). These institutions agreed to repurchase these crappy loans at par should they fail in any material respect to meet extensive warranties regarding their quality and characteristics.

In some cases, major investment banks profited multiple times off of the sale of the same crappy loans: 1) by bargaining down the price they paid for the crappy loans using the results from their own due diligence samples and then selling loans they knew were defective to investors at a profit; 2) by going back to loan sellers and shaking them down for settlements when the crappy loans went bad; and 3) by placing strategic bets against the securities themselves or the industry participants like monoline insurers who would be saddled with the losses from these crappy loans.

This and other irresponsible or outright fraudulent conduct has contributed to the complete collapse of the private mortgage market. More than 95% of new loans today are backed by our government, and thus by you, the taxpayer. There is no private market to speak of, save for a few jumbo deals with high-quality collateral, and there will be no serious private market for the foreseeable future.

There is a massive crisis of confidence – and deservedly so – surrounding our largest financial institutions and the rule of law. Our pension funds, college endowments, and insurance funds have taken the bulk of the losses thus far. And investors will not return to this market if some measure of loss sharing (I won’t go so far as to call it “justice”) is imposed on the banks that created and sold these crappy loans in the first place.

The federal government, for its part, has responded primarily by bailing out those same banks and “foaming the runway” for a soft landing. In actuality, the Treasury and the TARP bailout gave the banks such as soft landing that they largely bounced back without experiencing the healing pain of austerity, downsizing or – gasp – failure.

As illustrated in Neil Barofsky’s eye-opening new book, Bailout, this was the result of an intentional policy decision – the decision to inject capital and confidence into the economy by propping up the largest banks. This path has failed completely to boost the capital available for the middle class, and has succeeded only in postponing the correction and keeping bloated institutions on life support. Meanwhile, it has created perverse incentives for banks to misrepresent the ir financial health by manipulating LIBOR and take risky double-or-nothing-style bets to try to earn their way out.

ir financial health by manipulating LIBOR and take risky double-or-nothing-style bets to try to earn their way out.

Again, I am reminded of the scene in Being There where Chance is asked by the President to weigh in on economic policy:

President “Bobby”: Mr. Gardner, do you agree with Ben, or do you think that we can stimulate growth through temporary incentives?

[Long pause]Chance the Gardener: As long as the roots are not severed, all is well. And all will be well in the garden.

The roots of our biggest financial institutions are withered and rotting, and the costs of keeping them alive are mounting. And yet, with little appetite in Washington for another federally-funded bailout of Wall Street, and continued strains being placed on bank balance sheets, there is still hope for that much-needed correction to take place.

Tough Love

What will drive a correction in this market? Given the aversion of government to crack down on the banks with civil or criminal sanctions or redistributive tax and spend policies, the only hope we have is that private litigants will turn to the court system.

This process comes intuitively to most of us: if someone were to steal a significant amount of your money and refuse to return it when confronted, you would probably take the thief to court. It may take time and expense, but if you’re in the right, you should be able to recoup far more than your costs (hopefully a above-market ROI) through a judgment from the court (provided the thief is not judgment-proof). This is how the court system and the rule of law were designed, and the act of going through the court process not only helps the victims recover what’s rightfully theirs, but it helps the entire system by deterring future theft. The same can be said about enforcing contractual reps and warranties.

I believe our court system still largely functions as it was designed to, albeit more slowly than we might like. This is why I have been advocating for years for investors to get organized and enforce their contractual and common law rights to recompense.

In the putback space, contractual requirements of 25-50% voting rights for investors to have standing mean that investors must band together to make any progress. There have been several efforts to do so on behalf of investors, but most have fallen apart, save for attorney Kathy Patrick’s efforts on behalf of 22 institutional investors (more on that later).

The problem here is that there are intermediaries between those who are currently bearing the losses and those who should be bearing the losses. There are money managers who value their relationships with liquidity providers over the dispersed individuals whose money they manage. There are RMBS Trustees who likewise value their relationships with the banks that hire them over the Certificateholders whose interests they arguably have the obligation and sole power to protect.

This makes the process even more complex and tedious because it means that those whose money was stolen may be forced to sue the intermediaries for failing to act on their behalf in addition to, or in lieu of, suing the thieves themselves. That is already beginning to happen, and investors have made some encouraging strides in their suits against particularly obstreperous RMBS trustees.

So what about Kathy Patrick’s efforts that resulted in a proposed $8.5 billion settlement on Countrywide bonds, a proposed $8.7 billion settlement on ResCap bonds, and potential future settlements with other large banks? As I’ve discussed at length, this group is led by some extremely conflicted investors who are dedicated to preserving the status quo. They would like to create the appearance that they are doing something to enforce their own investors’ rights and recover some of their money so that they can avoid being sued themselves (see above) for wasting valuable claims and failing in their fiduciary duties to their investors.

But, they don’t want to do so much as to make it too painful for BofA, JPMorgan Chase and the other banks on whom they depend for financing in a variety of other areas. So, they put together a settlement at pennies on the dollar and hope to get the court to bless (read: rubber stamp) it.

Sure, there are investors who oppose these global settlements, but the number that is willing to speak up is small and dwindling. Walnut Place, represented by Grais and Ellsworth, was one of the most vocal and active objectors in the $8.5 billion Countrywide settlement. They had intervened, in part, to preserve their claims in their separate putback lawsuit against BofA. However, when they’re separate suit got dismissed for failure to comply with procedural prerequisites, and the dismissal was upheld on appeal, Walnut Place dropped its objections to the $8.5 billion deal and eventually put its Countrywide MBS holdings up for sale.

Rest assured that the Steering Committee of intervenors in the settlement has not disbanded; however, there is now one fewer vocal investor driving the Committee’s efforts. It appears that AIG, represented by Reilly Pozner, and the Triaxx CDOs, represented by Miller Wrubel, are stepping into Walnut’s place, and ably representing the remaining objectors. But many investors have kept quiet as this deal has been foisted upon them, and those who are spending money to object are starting to question whether it’s worth their time and money.

In their more cynical moments, investors are starting to feel that fix is in and question whether they’re throwing good money after bad. Plus, we have heard scant little from the New York and Delaware Attorneys General, who after fighting so hard for the right to intervene, have been little more than window dressing in the Article 77 hearings over the last few months.

It remains to be seen how difficult the Steering Committee can make things for BofA and BNYM over the next year by demanding detailed discovery. Already, the Committee has succeeded in obtaining court approval to review 150 Countrywide loan files for breaches of reps and warranties, over the strenuous objections of BofA. Though not a statistically significant sample size, the review could uncover indications of a significantly higher rate of breaches of reps and warranties among Countrywide trusts than was assumed by Bank of New York when reaching the settlement figure. This, in turn, could prompt Judge Kapnick to order a more extensive sampling of loan files.

Most recently, Reilly Pozner filed a letter in MBIA v. Countrywide (h/t Manal Mehta), seeking to persuade Judge Bransten to unseal reams of potentially damaging documents regarding BofA’s purchase of Countrywide, which were unearthed by MBIA after years of hand-to-hand discovery battles in that case. On Monday, Bloomberg LP also threw its hat into the ring, filing a motion for leave to intervene to encourage Judge Bransten to remove confidentiality restrictions on the documents (another h/t Manal Mehta). Judge Bransten has set a hearing for today to consider this issue, which beyond having major ramifications for MBIA in this case, could provide valuable ammunition to all plaintiffs seeking to hold BofA accountable for Countrywide’s liabilities.

But as far as the Article 77 case goes, it’s hard to gauge just how much evidence Judge Kapnick would require to find that BNYM’s proposed settlement is unreasonably low. MBIA v. Countrywide should certainly provide a fair amount, if it goes much further without settling. While the Article 77 should continue to yield interesting developments for the next year or so (remember that Kapnick has now set an approval hearing for May 2013), it’s starting to look more and more like this deal will go through as proposed. Barring a major collective action push by institutional investors, it’s only a matter of time before Patrick begins cutting similar deals with the other major issuers.

Don’t Put Your Trust in Trustees

What can we expect from trustees like Bank of New York Mellon, who have the strongest legal standing to enforce breaches of reps and warranties? BNYM recently filed an action against WMC Mortgage and GE Mortgage Holding (h/t Manal Mehta), joining the ranks of trustees like Deutschebank, Wells Fargo, and U.S. Bank (going after BofA and WMC), which have filed putback lawsuits on behalf of investors.

We’ve also seen BNYM negotiate an $8.5 billion settlement with Countrywide. Do these developments mean that trustees are finally acting in investors’ best interests? The short answer is: not really.

BNYM is essentially motivated by the same fears as the major institutional investors – doing nothing would expose the trustee to liability for wasting valuable claims. To avoid that, trustees like BNYM want to take some action that makes it look like they addressed the problem. This is especially true when motivated investors are taking aggressive action behind the scenes to review loan files, share their findings with trustees, and petition those trustees to take action. The trustees can (and did) drag their feet for a while, but at some point they have to act or risk becoming the target of a lawsuit. This doesn’t mean that trustees will suddenly find their moral compass and start taking action on behalf of the bulk of investors who aren’t hounding them day after day to take action.

Keep in mind that trustees are “bankers’ banks,” providing banking services for the largest banks, like BofA (which accounts for 60% of BNYM’s custodial business). BNYM is paid relatively little to oversee a massive dollar value of custodial accounts. BNYM simply wants to keep BofA happy and avoid incurring liabilities that would dwarf what they were paid to oversee RMBS Trusts.

Enter Kathy Patrick with a sweet deal – float our minimal settlement to the court and BofA will indemnify you for any losses. This allows the deals to carry the imprimatur of fairness without trustees having to bite (or cripple) the hands that feed them. Meanwhile, nobody can argue that the trustees aren’t doing anything to help investors – in fact, trustees and banks can use these types of settlements to argue that investor claims are improper or “premature” because trustees are actively enforcing putback claims.

As I’ve written before, this is the end game scenario as pictured by Kathy Patrick and her merry band of investors – enter into favorable global deals for issuers that bind all investors. This allows investors and trustees to avoid liability for ignoring their fiduciary duties while spraying more foam on the runway for the major banks with which they do significant business. The banks get to put their mortgage issues behind them, the investors get a small payday, Patrick gets a huge payday, and everybody wins. Everybody, that is, except taxpayers, investors and the housing market.

A Chance for Optimism?

Chance the Gardener: Yes! There will be growth in the spring!

Benjamin Rand: Hmm!

Chance the Gardener: Hmm!

President “Bobby”: Hm. Well, Mr. Gardner, I must admit that is one of the most refreshing and optimistic statements I’ve heard in a very, very long time.

If U.S. institutions are proving to be reluctant to pull the trigger on collective efforts, and therefore will let their claims go for little in return, what hope do we have that anyone will compel this much-needed correction to take place? On the investor side, the lone hope appears to be the European banks.

European institutions, and in particular the large German land banks, hold hundreds of billions of dollars in U.S. private label MBS. Many of the holders are German “bad banks” that have been split from the solvent portions of the institutions and are receiving pressure from their regulators to take action to recover their losses. Articles have begun to appear in the German press questioning what these banks are doing to address their massive losses, such as an article that appeared last month in Handelsblatt entitled, “Deutsche Landesbanken erwägen gemeinsame Klagen gegen US-Institute. Es geht um Milliarden, doch das Vorhaben birgt Risiken” (roughly translated as “German Landesbanks consider joint action against U.S. firms. It’s about billions, but the project is risky”).

The European investors are not as dependent on large U.S. banks for liquidity as their U.S. brethren, and there is not nearly the same level of political aversion to taking on TBTF institutions as there is in the U.S. so there is some reason to believe that these European institutions will enter the litigation fray. Indeed, over the last six months, we have started to see increasing legal action in the U.S. by European institutions focused on MBS losses (see suits by the German Landesbanks or Sealink Funding, for example); however, these suits have tended to be comprised of fraud claims only.

Fraud claims are generally characterized as “easy to file, hard to win” because, while they do not require that investors overcome onerous procedural hurdles, they also have heightened pleading requirements and necessitate proof of knowledge of falsity, intent to mislead, and detrimental reliance by the plaintiff. While there is some evidence to support these findings, the suits would have a much greater chance of success if the Europeans did the leg work to organize and bring contractual-based rep and warranty claims.

While it sounds like many of these European institutions are still on the fence about bringing aggressive legal action against U.S. institutions, what’s clear is that if the collective investor movement will not come from Europe, it may not at all. Investors must truly speak now or forever hold their peace. The window of opportunity to object to contrived global settlements or file their own claims will slam shut within a year.

And if investors think that all they stand to lose is the right to pursue legal claims to recover existing MBS losses, think again. To the contrary, if investors show they’re not willing to band together to enforce their rights, their assets will continue to be plundered and pillaged in increasingly creative (some would say diabolical) ways.

Take the ongoing debate surrounding eminent domain as Exhibit A. The proposal originally floated by Mortgage Resolution Partners and gaining steam in municipalities all over the country proposes having local governments seize performing but underwater mortgages at 75-80 cents on the dollar. These mortgages would then be restructured and sold to new investors, allowing homeowners to refinance into positive equity situations.

Bondholder and banker advocacy groups have raised hell, but that hasn’t stopped these proposals from moving forward. Now, there is a constitutional requirement that governments pay just compensation if they seize property, but who will stand up and challenge these takings? Trustees certainly don’t have the incentive to do so, and have all but proven as much. And investors may not even have standing to do so in many states if they don’t unite and form coalitions of 25-50% (some states provide only trustees with standing to participate in condemnation proceedings).

Banks, backed by lobbying groups like SIFMA and ASF, could still challenge, as they are concerned that their second lien holdings could be seized along with underwater firsts. But should plan proponents agree to resubordinate these second lien holdings to the new, restructured senior liens, bank resistance would probably evaporate. This, according to many with knowledge of these plans, is the most likely direction of these eminent domain proposals. This would mean distressed second liens held by banks would be recapitalized at investor expense, in yet another closet bailout of our struggling financial institutions.

would mean distressed second liens held by banks would be recapitalized at investor expense, in yet another closet bailout of our struggling financial institutions.

So, as bad as things might look in the garden for investors, they must recognize that things could still get worse. Now is the time to take stock of the root system in the financial markets and take proactive steps to clear out the detritus of failed business models if we ever want to see a new spring of growth in U.S. housing.